Cleaning Operations

BOK | Part 2 | Operations and Maintenance

- Introduction

- The Mission and Purpose of Custodial Services

- A Road Map for Successful Custodial Operations

- Custodial Audit

- Benchmarking Processes

- Staffing the Custodial Operation

- Cleaning as a Process

- Toward Continuous Improvement

- The Environmental Role of Custodial Services

- Toward the Future

- Selling Our Story—The Value-Added Component

- Putting It All Together

- Summary

- Author

Updated: August 2024

This chapter was updated in 2024 by Steven Gilsdorf CEFP, from a previous BOK chapter by Alan Bigger, titled Custodial Services.

Visiting college and university campuses across the nation is a unique and invigorating experience. Though the primary role of educational institutions is advancing the education of students and conducting research, no two campuses are the same. Some campuses have one million square feet or less of building space, and others have tens of millions of square feet. Some campuses are older, and others are newer; some may be urban and others rural; some may cover massive acreage of land, and others may be crammed between existing city buildings.

Regardless of the differences, some measures come to mind that can impact a visitor’s perception of any campus. First impressions are lasting impressions, and when one walks on the campus for the first time, the appearance of the grounds and the buildings will have an immediate impact on the visitor, the student prospect visiting the campus, or the student’s bill-paying parents. A growing body of research clearly indicates that the appearance of the grounds and the cleanliness of buildings have a direct impact on student recruitment and retention at institutions of higher education (David Cain, Ph.D., and Gary L. Reynolds, P. E., “The Impact of Facilities on Recruitment and Retention of Students,” APPA Facilities Management Article–Part One, and APPA Facilities Management Article–Part Two, 2006).

An institution that wishes to attract the best and brightest students and researchers needs to attend to these details and maintain the optimal level of appearance. Several research projects commissioned by APPA have highlighted and clearly documented the importance of the appearance of grounds and the appearance and cleanliness of buildings for students. A study by Jeffrey L. Campbell, Ph.D., and Alan S. Bigger, M.A., Cleanliness & Learning in Higher Education (APPA, 2008), emphasized the correlation of students’ perception of the impact of cleanliness on the learning environment.

In addition to research conducted about the visible impact of cleaning on campus, Dr. Charles P. Gerba of the University of Arizona has conducted some solid research. A growing body of research demonstrates a correlation between clean facilities and lower absenteeism in institutions, as exemplified by Dr. Gerba’s study, Cleaning Desktops and Other Classroom Surfaces Reduces Absenteeism, which chronicled a 50 percent absenteeism reduction when certain measurable cleaning processes were practiced.

Viruses that cause influenza, diarrhea, and respiratory illness commonly reside on school-age children’s desktops and other surfaces in educational facilities. Every time these surfaces are touched, viruses can be transmitted to healthy individuals. Office buildings are not exempt. During the cold season, Dr. Gerba’s group found cold viruses on surfaces in a third of offices across the country. Thus, not only does cleaning complement a student’s ability to learn, but cleaning can also contribute to a student’s overall health. One of the most significant contributions of Dr. Gerba’s research is that it documents the existence of a clear relationship between cleaning and health.

As the body of research demonstrating the importance of custodial operations at institutions grows, there is increasing competition among institutions to attract the best, and parents and students are expecting the best at an affordable price. Today’s students are savvy consumers as they select the institution they wish to attend. When students visit campuses on recruitment tours, they are looking closely at not only the academic offerings of an institution but also the types of resources that the mix of buildings offers on campus, and the cleanliness— or lack of cleanliness—could significantly impact their evaluation of these buildings. Keeping buildings clean is an important element in bringing and retaining students to our campuses.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought building cleanliness to everyone’s forethought. Establishing the fact that campus cleaning produces a healthy building, and not just one that appears clean, became a discussion for board members and a tool for recruitment. In the public’s eye, the correlation between cleaning and health became all too apparent.

Despite the mounting empirical evidence that the appearance of the grounds and buildings and the cleanliness of the buildings are important in recruiting and retaining students and providing for their health, there is an increasing, and seemingly insatiable, desire for these operations to become more efficient and less costly. Those desires are to be implemented without having a significant impact on the level or quality of services provided.

APPA’s Operational Guidelines for Educational Facilities—Custodial, 4th edition (2023) documents quite clearly that there is a law of diminishing returns. We may seek to decrease operational overheads and clean more space with fewer custodians, yet as we do so, and as cleaning is done less frequently, appearances will suffer. In this environment, it is critical that managers understand the important role of custodial operations and that there is a clear and inseparable relationship between custodial services and the academic mission of our institutions.

One of the greatest challenges that a custodial manager faces is communicating the mission and purpose of custodial services to the administrative hierarchy. It is important that the mission of the custodial services be linked with the mission of the institution. The primary mission of custodial services is to provide a clean and healthy environment that supports and adds value to the educational mission of a campus. The custodial operation brings value to the setting of the institution by enhancing the appearance of the buildings and presenting an acceptable level of cleanliness that is supportive of and synergistic with the learning mission of the institution and its impact on student recruitment and retention. The policies, procedures, and programs that custodial services implement will support that mission.

The roadmap for successful custodial operations is the continuous improvement process. The high-performing organization takes an inventory or audit of where it is today, forecasts where it seeks to go (the goal) and establishes metrics with which to measure progress. The use of longitudinal data is a necessary and effective tool to guide the organization as it heads into the future.

The purpose of a custodial audit is to document past and current practices, and to determine the effectiveness of those practices in supporting the mission of the department and institution. Chapter 7 of APPA’s Operational Guidelines for Educational Facilities—Custodial, 4th edition, provides an overall methodology to assist in auditing an operation and especially how to determine a facility’s level of appearance.

The Fourth edition introduces additional descriptions that provide continuity with the Operational Guidelines for Maintenance and Grounds. The descriptions provide further clarity when discussing the levels of service with those not familiar with the APPA levels. The audit tool establishes a baseline for an institution’s level of cleanliness, and the audit process assists in:

- Developing a baseline of cleanliness using APPA’s five appearance levels, displayed in Figure 1

- Evaluating the results and effectiveness of modifying procedures

- Establishing performance evaluations and a feedback process

- Creating a quality assurance program that not only provides feedback to the custodial team member but also includes customer feedback

Figure 1. Custodial Appearance Levels

Level 1: Orderly Spotlessness—Showpiece Facility

- The floors and base moldings shine and/or are bright and clean; the colors are fresh. There is no buildup in corners or along walls.

- All vertical and horizontal surfaces have a freshly cleaned or polished appearance and have no accumulation of dust, dirt, marks, streaks, smudges, or fingerprints. Lights all work, and fixtures are clean.

- Washroom and shower fixtures and tile gleam and are odor-free. Supplies are adequate.

- Trash containers and pencil sharpeners hold only daily waste and are clean and odor-free.

Level 2: Ordinary Tidiness—Comprehensive Care

- The floors and base moldings shine and/or are bright and clean. There is no buildup in corners or along walls, but up to two days’ worth of dust, dirt, stains, or streaks can be present.

- All vertical and horizontal surfaces are clean, but marks, dust, smudges, and fingerprints are noticeable upon close observation. Lights all work, and fixtures are clean.

- Washroom and shower fixtures and tile gleam and are odor-free. Supplies are adequate.

- Trash containers and pencil sharpeners hold only daily waste and are clean and odor-free.

Level 3: Casual Inattention—Managed Care

- The floors are swept or vacuumed clean, but upon close observation, there can be stains. A buildup of dirt and/or floor finish in corners and along walls can be seen.

- There are dull spots and/or matted carpets in walking lanes. There are streaks or splashes on the base molding.

- All vertical and horizontal surfaces have obvious dust, dirt, marks, smudges, and fingerprints. The lamps all work, and the fixtures are clean.

- Trash containers and pencil sharpeners hold only daily waste and are clean and odor-free.

Level 4: Moderate Dinginess—Reactive

- The floors are swept or vacuumed clean but are dull, dingy, and stained. There is an obvious buildup of dirt and/or floor finish in corners and along walls.

- There is a dull path and/or obviously matted carpet in the walking lanes. The base molding is dull and dingy, with streaks or splashes.

- All vertical and horizontal surfaces have conspicuous dust, dirt, smudges, fingerprints, and marks.

- Lamp fixtures are dirty, and some (up to five percent) lamps are burned out.

- Trash containers and pencil sharpeners have old trash and shavings. They are stained and marked.

- Trash containers smell sour.

Level 5: Unkempt Neglect—Crisis

- The floors and carpets are dull, dirty, dingy, scuffed, and/or matted. There is a conspicuous buildup of old dirt and/or floor finish in corners and along walls. Base molding is dirty, stained, and streaked. Gum, stains, dirt, dust balls, and trash are broadcast.

- All vertical and horizontal surfaces have major accumulations of dust, dirt, smudges, and fingerprints—all of which will be difficult to remove. Lack of attention is obvious.

- Light fixtures are dirty with dust balls and flies. Many lamps (more than five percent) are burned out.

- Trash containers and pencil sharpeners overflow. They are stained and marked. Trash containers smell sour.

However, to develop baselines from whence your organization came, it is important to go back through your records and clearly document certain key pieces of information. Data from the previous five years (more years would be more meaningful) should include the following elements:

- A building inventory of how many buildings have been maintained and their cleanable square feet over the years. The gross square feet method provides only a thumbnail sketch; the cleanable square feet method is much more effective, as there are many areas and spaces in a building that a custodial staff may not clean.

- A staffing inventory that has been used to clean these buildings over the years that are being audited.

- The categories or types of spaces maintained, such as classrooms, offices, and public areas.

- The square feet cleaned per custodian during those years.

- The cost per square foot to maintain these spaces, with labor costs per square foot and supplies cost per square foot.

- The level of appearance or quality of service provided during the years.

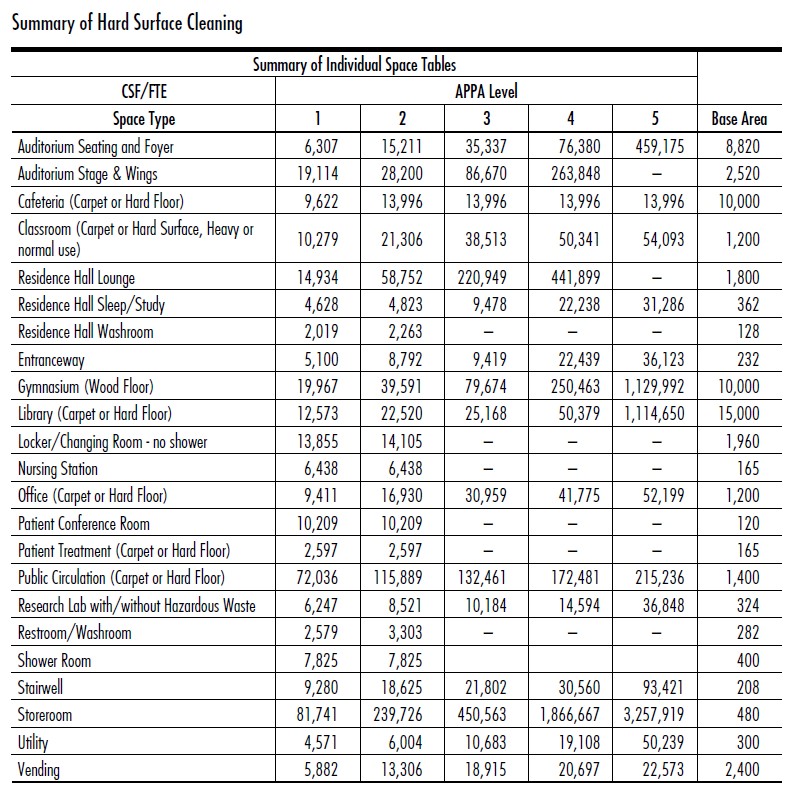

In 1992, APPA published the first edition of the Custodial Staffing Guidelines, in which the levels of appearance were originally established and defined. The guidelines originally defined 10 room types. APPA’s current guidelines provide for 23 room types; the ideal would be to correlate spaces as closely as possible to those room types. The 23 room types, productivity associated with each room type, and service level are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. APPA Staffing Service Levels

A cleaning audit should document—albeit retroactively—the level of service provided over the years. APPA’s guidelines provide a weighting system that can be used during the audit process, as not all areas or spaces may have equivalent weight.

Conducting this audit will help establish a baseline for operations and document activities that have taken place over the years. The audit will provide the total square feet cleaned, the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) employees that it takes to clean the space, the average square feet maintained by each FTE employee, the cost per square foot for labor and supplies, and the APPA level of appearance that has been provided by these services. One can take these data in summary form to indicate to the administration the effectiveness of the organization.

Once the audit has been completed, there will be a clearer understanding of the organization’s performance history, and it will be easier to start considering what direction the department needs to move in the future. How is the organization really doing? Is the organization more or less effective and efficient than comparable institutions?

Inwardly, we may think that we are the best anywhere, but is custodial services truly providing the institution the best value for the resources expended on operations? Once baseline data for the organization is known, comparisons can be made between the organization and peer or comparable institutions and against some industry standards such as those provided by the following sources:

- APPA’s most current edition of the Facilities Performance Indicator (FPI). This survey is updated yearly, and institutions can participate in the survey by plugging in its data, then comparing themselves with like or unlike institutions. For more information, visit www.appa.org.

- APPA’s appearance levels and anticipated productivity associated with each room type and appearance level. Organizations can be compared using this information as a baseline.

- The International Sanitary Supply Association at www.issa.com provides useful benchmarking data.

- Several software packages are available on the market to help with data collection and the benchmarking process.

The custodial operation is very labor-intensive, and work must be accomplished with and through people. As a rule of thumb, excluding benefits, approximately 90 percent of custodial costs are in labor and 10 percent in cleaning supplies. Knowing these cost breakdowns, the effective management of the custodial labor becomes vitally important. At this stage, it is useful to know the elements that go into the custodial equation that impact the cost of operations.

- The tasks to be performed—such as dusting furniture, mopping floors, or vacuuming carpets.

- The frequency with which the tasks are going to be performed, for instance, daily, alternate days, weekly, biweekly, or monthly.

- The time allocated to complete the work to be performed. No matter how efficient the performance of a task may be, the task takes time.

- The type(s) of space to be cleaned. There are significant differences between hallways and restrooms, classrooms, and research laboratories.

- The level of appearance expected. APPA’s five levels of appearance seek to define levels of clean.

- The types of equipment that are used. For instance, if a custodian mops a floor with a standard or microfiber mop, it will take significantly more time than if the area is cleaned with automated equipment such as an auto scrubber.

- The amount and cost of materials necessary to accomplish the task(s).

- The hourly labor cost for time expended to complete the task(s).

- Variables such as climate and geographic location, age and complexity of facilities, training programs, types of space and usage of that space, age of facility, hours of usage, and traffic density.

The staffing models may vary from institution to institution. For instance, one institution may use a zone cleaning method, whereby one custodian is assigned to clean a certain area, such as two floors of a building, day after day. That zone is the person’s responsibility to clean each day. Another institution may opt for a crew cleaning concept, whereby a crew goes into a building with perhaps four people cleaning eight floors. They work together to accomplish the tasks, literally sweeping through the building from top to bottom. Both methods—zone cleaning and crew cleaning—may be defined as self-directed work teams, with each member holding the whole group accountable.

The use of team cleaning, sometimes referred to as High Performance Cleaning, is a more refined process, where cleaning specialists flow through spaces to be cleaned with an assigned set of focused tasks to accomplish. One may perform all the dusting, another vacuuming, one taking out the trash, and someone may specialize in restroom cleaning. Team cleaning is becoming increasingly popular as people become specialists at their task assignments. Ultimately, all team members can be cross trained to perform all specialties.

One method may not work in all areas, and a hybrid of staffing methods may be required. However, the systems that work the best are those that build the self-worth and agency of the custodians. Systems that make the custodian feel supported and empowered to have a say in how work is going to be performed and that provide the custodians with a sense of accomplishment at the end of each day.

How does a manager determine how many custodians are needed to staff a building or an operation? There are various models available; however, all models need to take into consideration the tasks to be performed, the frequency with which tasks are to be performed, the time allocated, and the expected appearance level that is acceptable once the work has been performed. The following are some of the methods that may be considered:

- Raw-square-footage method. Simply take the total number of square feet (e.g., 100,000 square feet) and divide by an expected productivity standard, such as 25,000 square feet per custodian per day. The resulting staffing needed is four custodians. However, this does not take into consideration the complexities of the space, nor does it establish the acceptable level of appearance after the cleaning process has been completed.

- Fixture method. Some staffing systems are based on a complete inventory of every fixture in a building and the time it takes to clean each fixture, based on industry standards. Even though highly detailed and scientific, this system does not identify the acceptable level of appearance after the work has been performed.

- Type-of-space method. This process includes the elements discussed earlier and is more complex to compute; however, the outcome is more realistic and accurate. An inventory is taken of all room types, the tasks to be completed, the frequency of those tasks, and the times needed to accomplish those tasks. This system is based on the 23 room types defined by APPA and includes the tasks, frequencies, and times necessary to complete the work at various levels of appearance. By using this system, the manager can project the anticipated outcome of appearances based on staffing levels. (See Figure 2.)

The good news for managers is that various computer modeling programs are available to assist in computing staffing assessments and projections for an institution.

When is the right time to clean? Increasingly, university buildings are becoming 24-hour operations, seven days a week. However, in most cases, the funding available to the custodial manager may enable a facility to be cleaned only on one, eight-hour shift, or—at most—two shifts. Funding may only be available for five days a week, or the manager may have to stagger staffing to cover weekends or holidays. In most cases, institutions are expected to provide maximum cleaning while using minimal staff.

- Day cleaning. This method is increasingly popular, as it minimizes the use of excessive energy since heating and air conditioning systems are on (no need to heat or air condition at midnight when there are only a few people in a building); lighting needs are minimal; most people perform better and feel more valued if working when they are visible; the customers tend to be more satisfied if they see the custodian and can have items corrected immediately. Also, day work tends to be more family-friendly. It provides employees with a degree of self-management of their time and performance, as they are constantly observed by customers. Potential downsides of day cleaning are that it is harder to clean spaces that are occupied or when the cleaning process is disruptive. Work gets missed if occupied rooms are not revisited to be cleaned later. Customers may find that cleaning during the day interferes with business operations if cleaning equipment is noisy or dusting is disruptive to an office’s workflow.

- Late-night cleaning. Generally, the buildings have less traffic, and there is a greater ability to clean larger areas with less disruption. The downsides are many—the building systems must be fully functional; increased management attention must be provided as humans, in general, are not wired to perform during hours of darkness, even though some people do enjoy night work. Custodians are not visible to many customers, who may assume that if the custodian is not visible, the work is not being performed. Also, night work tends to interfere with the life cycles of homes and families.

- Swing-shift cleaning. This shift affords the custodial staff that works in the late afternoon and evening an opportunity to interface with customers before they leave for the day, clean offices after people leave, and, in most cases, clean classrooms and common areas with limited disruption. However, this shift is constantly being squeezed with longer hours of operations for buildings and increased student and researcher presence in buildings. The shift does tend to split the day and night for employees; some like this, yet others find it to be disruptive to their lifestyles.

Which shift staffing works the best? That must be determined in conjunction with the customers and employees to ensure that shifts are optimized to meet institutional and stakeholder needs.

Far too often, cleaning has been assumed to “just happen.” Hire employees, provide them with basic equipment and supplies, a checklist of what to do, and send them out to clean a building. It is becoming increasingly evident that if institutions want clean facilities, custodians and their managers must have a thorough working knowledge of the cleaning process. What are the key elements of the cleaning process that hold a custodial operation together and ensure that the custodial organization is operating effectively and efficiently in a cost-effective manner?

- A clear vision of the role of cleaning in the operation of custodial services and the educational mission of the institution. The custodial staff plays a critical role in the educational mission. By keeping the facilities clean, the custodians contribute to student recruitment and retention, the health of the community, and the creation of an environment in which the university stakeholders can work, study, and play.

- Detailed policies and procedures for the cleaning operation. A sign in a hospital conference room stated, “If it isn’t documented, it didn’t happen!” The same is true for custodial operations. If policies and procedures are not clearly described, it is unreasonable to expect correct performance, proper behaviors, or efficient operations to automatically be the outcome.These detailed procedures make conversations with customers easier by setting their cleaning expectations. By having this knowledge up front, customers are less likely to raise false red flags about building cleanliness and save their complaints for true deficiencies. If office cleaning is to occur at 11:00am, complaints about no custodian being seen at 9:00am become easy to answer.

- Clear job expectations. Clear and precise job descriptions must be developed so the custodians know their expectations. Job descriptions are just the beginning; having additional training on how to handle customer requests can introduce additional levels of personal agency for the custodian. This also allows for more efficient and effective customer service, lessens the need for the supervisor to visit with customers for every request, and provides a process for how the custodian can redirect requests that are not easily accommodated.

- Precise job assignments. The custodians should have precise job assignments that describe place and timing so they know the tasks that must be performed each day. Job assignments should also allow enough flexibility to accommodate the variability of cleaning needs that arise. For example, the general classroom will take significantly longer to clean after a student organization holds its monthly arts and crafts night.

- Measurable standards. Custodians should be provided definitions of cleanliness for each given task. APPA’s five levels of appearance are a good starting point. The standards should be observable, measurable, consistent, and realistic. The manager should clearly explain these standards.

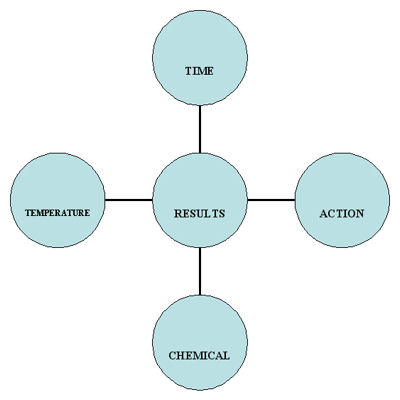

- Chemical use. The use of all chemicals should be explained, along with the role of Safety Data Sheets (SDS), personal protective equipment (PPE), and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rules and regulations. Safety Data Sheets should be provided in physical form at the location being used in case of emergency. If someone gets a chemical in their eye, having the only copy safely in the main office helps no one.Custodians need to know that chemicals do not automatically work. Four key elements—time, action, chemical, and temperature (TACT)—have to interact to enable chemicals to perform properly. These elements are listed below and displayed in Figure 3.

- Time: All chemicals take time to work effectively, and this is especially true for disinfectants. The industry calls this “dwell time.”

- Action: Just splashing a chemical on a surface does not release the soil. Action is necessary, such as the action provided when wiping a surface with a microfiber cloth or the turning of the floor pad by the auto scrubber.

- Chemical: Chemicals need to be mixed properly and in accordance with the manufacturer’s directions. Manufacturers provide clear directions about the dilution ratio of chemicals, such as half an ounce of chemical to a gallon of water, expressed as a ratio of 1:256. If mixed properly, the chemical will perform to expectations. However, if chemicals are not mixed properly, surfaces can be damaged, chemicals wasted, and the health of employees can be adversely affected through overexposure to the chemicals and odors caused by the chemicals, as well as exposure to the possibility of chemical burns or severe allergic reactions. Chemicals that are mixed improperly can leave residue films behind and make surfaces sticky and will not necessarily remove dirt. Different chemicals should never be mixed, and all chemical containers and secondary containers need to be properly labeled to meet or exceed OSHA requirements.

- Temperature: Even though more chemicals are being developed to perform effectively in cold water, custodians should read manufacturers’ directions, as some chemicals perform better at certain temperatures.

Figure 3. The TACT Model

- The use of equipment. The right equipment used the right way will facilitate the right results. The reverse is true as well. The wrong equipment used the wrong way will produce the wrong results. It is important that custodians be trained to use the correct equipment safely and properly for any given task. Too often, floors are damaged by operators using pads that are too abrasive, or walls are damaged because the operators of buffers or auto scrubbers are not properly trained in their use and lose control of the equipment or operate equipment in a less-than-careful manner.

- Proper training. It is imperative that proper training be provided by qualified trainers for custodial staff from the first day on the job and continuing throughout their careers. Training must be ongoing, innovative, invigorating, inviting, and lead to ongoing improvement so that the custodial operation is on the cutting edge of evolving methods, procedures, and practices. There should be initial in-depth training programs for custodians, subsequent training in the field after the initial training, and refresher training to keep the custodial staff up to date on current processes. Training gets cut too often when budgets are tight. It is during tight economic times, when institutions expect more from staff, that they must invest time in training so staff can meet the increasing demands of their positions.

An active safety program. Custodial work is incredibly labor-intensive, and the proactive manager will ensure that active and participatory safety training is in place. Soliciting input from the people who perform the work is vital in the effort to minimize injuries. Safety training should be provided on all equipment, supplies, and processes. When an injury occurs, there should be a thorough review of the incident to reduce the risk of such an incident reoccurring. The use of a safety committee that consists of managers and employees who interact and investigate injuries together without violating confidentiality can be effective in decreasing injuries.

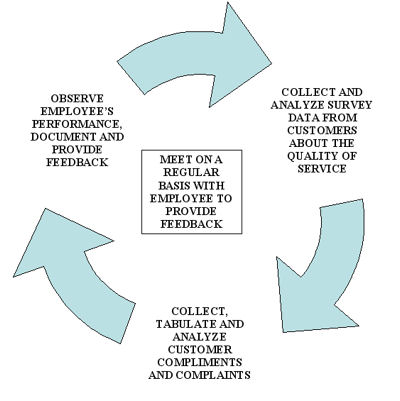

There is no doubt that custodial services are continually challenged to do more with less and to provide a consistent level of cleaning and service while containing costs. Thus, it is essential to implement an effective quality assurance program that will lead to continuous improvement. What are the elements of such a program in the operation of a custodial service?

- The communication of clear standards mentioned earlier.

- A basic quality assurance process where custodial managers visit job sites and evaluate the quality of work performed by the custodian, ideally with the custodian present, so that expectations can be clarified immediately. Some supervisors may use a pen-and-paper inspection form. However, phones and mobile devices are increasingly being used to document this process. The data can then be used for feedback, tracking, and comparison purposes.

- A visit to areas cleaned and a discussion with the customer as to what he or she sees. This is a vital step as it enables the manager to see the cleaning process through the eyes of the customer. It also provides a rich opportunity for the manager and customer to interact to clarify expectations.

- A series of random surveys to gather information from customers.

- A review of all compliments or complaints that have been received. These should be logged in by the office as they are received. These compliments and complaints should be tracked throughout the year. If the same customer keeps calling, the basic question of “Why?” should be asked and not dismissed. Both the compliment and complaint need to be investigated—one to figure out how to duplicate what is happening, the other on how to correct what is happening.

- Comparing the manager’s inspections against the compliment and complaint log. By comparing these elements, the manager will be able to develop a clearer perspective of the cleaning process, its effectiveness, and an action plan that will enrich and enhance the performance of individual custodians.

- An opportunity to praise is provided by this process as stellar performers are identified or improvements are made.

- An opportunity to promote improved cleaning and processes is provided by this comparison as areas of growth are identified. Opportunities for additional individual or group training may be developed as areas of weakness are identified.

- An opportunity for team building is provided as the manager works with the custodial team to identify the strengths of the organization, weaknesses of the organization, the opportunities for the organization to grow and excel, and the potential threats to the organization (problems, deficiencies, etc.), and to develop an action plan that will lead to the continuous improvement of the operation.

The key issue is to ensure that feedback is meaningful and timely and that employees are advised of the process so that improvements in quality and service are documented. The feedback process is really a continuous loop, as identified in Figure 4:

Figure 4. The Continuous Improvement Feedback Loop

Custodial services have a direct impact on the environment of the buildings and surroundings in which cleaning is performed. The custodian can actively contribute to indoor air quality by keeping areas clean and free of soils and biopathogens. Using chemicals correctly can minimize the release of volatile organic compounds. Recycling commodities generated in buildings reduces the amount of solid waste that goes into local landfills.

The custodial manager’s role is expanding, and he or she needs to become involved with ever-expanding opportunities to improve the environment and increase the sustainability of operations:

- Use of environmentally friendly products and processes. A growing list of products have received the seal of approval from organizations such as EcoLogo and Green Seal. The use of products certified by these organizations minimizes the environmental impact compared with products without this certification. Certified vacuum cleaners and other cleaning equipment can decrease the impact on indoor air quality and the environment. Innovative manufacturers are developing cleaning equipment that minimizes the large-scale use of cleaning chemicals and compounds by using engineered water as a cleaning agent. The advent of microfiber cloths and mops has greatly increased the effectiveness of the cleaning process without the use of harsh chemicals. Less chemicals lead to healthier building occupants, students, and, most importantly, cleaning staff. At institutions that have introduced greener cleaning practices, chemical exposure incidents, and even hospitalizations have decreased.

- Recycling. In a sense, recycling starts before a product is even purchased. Products should be purchased that have the least environmental impact and in quantities that will minimize discarded waste products. Also, strive to buy products in packaging that can be reused or recycled, like cardboard or recyclable plastics such as HDPE I and II, or on pallets made of cardboard, wood, or plastic that can be either recycled or returned to the supplier for reuse. If the purchase of products that cannot be recycled is avoided, those products will not be discarded in landfills at the end of the day.

- Indoor air quality. Custodial services will not degrade a building’s indoor air quality by purchasing chemicals with low volatile organic compounds. Using vacuum cleaners equipped with high-efficiency particulate air filters (HEPA filters) that minimize the distribution of dust particulates into the area will actually improve indoor air quality as dirt and dust are removed from buildings.

Cleaning equipment, supplies, and technologies continue to evolve, and it is the responsibility of the custodial services manager to stay on top of these issues. The following are among the evolving trends that will impact managers:

- Benchmarking. Organizations will increasingly need to compare themselves with their peers and institutions for comparison and growth purposes. As mentioned earlier, benchmarking is here to stay, and organizations need to measure and compare to continuously improve. Benchmarking should include peer institutions as well as dissimilar organizations so the custodial manager can become knowledgeable of the best practices that could be implemented in his or her operation.

- Measure of cleaning. Technology has been developed that will enable managers to measure the effectiveness of cleaning programs. APPA’s custodial guidelines and levels of appearance were a quantum leap in an industry that, up through the late 1980s, demonstrated little interest in any form of industrial quality measurement in the field of custodial operations, especially as it related to appearance levels or levels of cleanliness.As we move to the future, new measurement technologies are available, such as the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) meter (see Figure 5). This meter identifies ATP on a surface. According to Robert W. Powitz, Ph.D., MPH, “ATP is the primary energy transfer molecule present in all living biological cells on earth—its measurement is a direct indication of biological activity. Simply stated: no biological contamination, no microbial growth.” The advantage of the ATP meter over the traditional method of colony counts is that it provides data in real-time (i.e., seconds instead of days) and at a low cost. This provides immediate feedback and allows for quick corrective action as needed. Other measurement instruments are currently being used, such as handheld air-monitoring equipment, water quality monitoring meters, ultraviolet-revealing technology, and volatile organic compound measuring units.

Figure 5. ATP Meter

- A more scientifically based cleaning process. The custodial services manager will need to stay current with the research, such as that conducted by Drs. Gerba and Powitz mentioned earlier. A good starting point for custodial research is APPA; the Cleaning Industry Research Institute (CIRI), which was founded “to raise awareness of the importance of cleaning through scientific research” or the International Sanitary Supply Association.

- Moving toward cleaning the unseen. During the past decade, custodial services have been barraged with increased expectations to prepare to respond to viral outbreaks or pandemics. This requires an increased level of sophistication on the part of the custodial services manager. Not only must custodial services respond to make surfaces visibly clean (i.e., remove dirt and trash), but the expectation is that the invisible dirt or micro-organisms and bio-pathogens will also be removed. Custodial services are not just cleaning for appearances but cleaning for health. To accomplish this, the manager will need to implement a systems approach to cleaning that uses best practices to clean facilities and to measure the effectiveness of the cleaning program using a technologically sophisticated version of the old inspection process—the new process will measure the presence or absence of the unseen dirt. Such an approach uses scientific instrumentation to measure the effectiveness of the cleaning processes and requires the use of best practices, chemicals, and equipment to produce the final result: hygienically clean facilities, using processes and practices that address the philosophy of “cleaning for health.”

- Professional development. The custodial services manager of today needs to be a true professional and needs the skill sets to be successful in today’s environment. Involvement in the professional development process afforded by APPA is the ideal solution. APPA provides a professional development continuum of programs that will enhance a manager’s skills through programs such as the Supervisor’s Toolkit and the Institute for Facilities Management. Such training can pave the road for the custodial manager to become a Certified Educational Facilities Professional (CEFP).

During the past few years, managers have been exposed to training that indicates the need to understand the generational differences that impact the workplace. Such training has provided labels and statements that have been attached to describe and facilitate understanding of generational differences in an organization. One of the drivers for a recent generation has been the question, “What is in it for me?” This driver is also embedded in the culture of many organizations that ask, “What is in it for the organization?” or, in the case of custodial services, “What do custodial services bring to the table that benefits the organization?” Custodial services provide innumerable benefits to an institution that are worth repeating, not only to the reader but also to the administration of the institution. What are some of the value-added benefits that custodial services provide?

- An aesthetically appealing and clean environment that contributes to the learning process.

- A healthy environment that contributes to the health of individuals and the institution.

- A safe and secure environment—custodians are an extra set of eyes and ears for the institution and provide an additional level of security to the campus community.

- An ambassador for all—custodians are spread throughout the campus and can be ambassadors of goodwill to students, visitors, faculty, and staff who otherwise may not have contact with university personnel.

- An environmental legacy—custodians remove trash, recycle products, remove dirt from buildings, and use environmentally friendly chemicals to improve indoor air quality and provide cleaning services for a healthy environment in campus buildings.

A case study illustrates this: a university was going through a budgetary tightening process, and the institution’s financial officers were concerned with lowering the facilities management expenses. The facilities managers reviewed the custodial operations.

On one side of a single piece of paper, they laid out the impact if the custodial budget were cut, the number of employees affected, and the levels of cleanliness that would be provided. The discussion included how many custodians would be required for Levels 1 through 5, the costs, and the descriptions of the appearance levels. The university’s budget personnel and administrators could visualize the outcome by cutting the custodial budget.

The decision was made to change office cleaning from daily to alternate-day cleaning, which provided adequate savings and had a limited impact on employees. Staffing was adjusted when employees retired or left the institution. The service cuts were implemented in the offices of the president, provost, and all senior administrators and then gradually across campus to enable the cuts to be made by attrition of personnel.

The facilities manager drafted a communication from senior university officials to campus personnel that was sent to everyone impacted by the service levels. The budget issues were clearly explained, and the impact of the service levels was communicated to all stakeholders.

During this process, facilities management staff met with the custodial staff to keep them advised of the pending changes, their need, and the impact on their work schedules and long-term employment. Once the message was communicated to the entire campus, facilities managers and supervisors met with individual departments and offices to streamline the service. Service-level charts were available to all stakeholders, clearly indicating what cleaning tasks would be performed and how often. The customers understood the reasons and supported the mission of the custodial staff.

As expectations for service levels increase and funding for the services stays the same or decreases, facilities managers must spend time and effort communicating the impact of fiscal decisions to all stakeholders. The discussions should include all levels, from custodian to custodial supervisor, from facilities managers to senior university officials, and from senior officials of the campus at large so that all clearly understand the rationale behind changes. Obtaining “buy-in” across campus will enrich the relationships between all stakeholders.

The managers of custodial services are faced with increasing challenges to do more with less and to provide equivalent or better service levels to institutions when funding for such services is decreasing. They must be creative and flexible to provide levels of services that meet or exceed the stakeholders’ needs across campus. To do this, the custodial services manager must be a facilities professional who is on top of his or her game professionally and on the cutting edge of evolving technology and innovations. By so doing, the custodial services manager will be able to manage a lean, green, cleaning machine that provides effective and efficient services in a manner that is environmentally sustainable for the future.

Author

Steven Gilsdorf, CEFP

Western Michigan University

Steve is a 20 year veteran of facility management. Over the past decade, he has spent his time as an in-house service provider, including overseeing Maintenance, Landscape, Transportation, Power Plant and Custodial, where he believes all FM service begins. Steve has served with MAPPA and APPA for half a decade in various roles—information & communication committee, mentor task force, MAPPA Board, APPA Board and MAPPA President.

Back to BOK